Vernissage

12th March 2022 from 3pm

Exhibition

13th March 2022 – 8th May 2022 (extended)

Venue

SGA Chengdu, no.2 Building 29, Tianfu Changdao, 16 Shengtong Street, Gaoxin District, Chengdu, China.

Artists

Huang Yuanqing, Pan Wei, Xue Song

Academic Moderator

Gu Heng

Curator

Wang Yu

▃

Huang Yuanqing, Pan Wei, and Xue Song — three artists bearing dynamic and diverse styles — come together in the common theme of 'Chinese characters' to offer their interpretations of the relationship between the semiotics of text and fine art.

The written word represents a profound dilemma for both contemporary art and artists alike. American author and journalist Tom Wolfe once ridiculed modern art as "completely literary," considering it a rushed appeal to the spectacle of fashionable ideologies. Similarly, French sociologist Jean Baudrillard openly claimed contemporary art as "null," guilty of "confiscating banality, waste, and mediocrity to turn them into values and ideologies." Such mounting criticisms left artists fumbling for a suitable response. However, their silence does not mean they agree with Wolfe and Baudrillard, but that they would have to use words to reason the contrary. It is the equivalent of absolving an argument between a chess player and a boxer through a physical duel; victory is clear and meaningless.

Interestingly, ancient China observed a period of infatuation between words and fine art. When Chinese characters surged during the Shang dynasty, emperors were keen to seek divination from Wu practitioners, or shamans, in topics ranging from the location of a capital city to something as minor as a toothache. To attend their requests, Wū-practitioners: the dancers would summon heavenly spirits with a ceremonious dance; colloquialists would appease them with their moving chants; and historians would humbly inscribe the divine answers onto oracle bones. It was certainly a joyous and harmonious period for those who practised Wu-ism. While at its prime--"constant dancing in the palace and drunken singing in the chambers" -- artists also played a fundamental role. As an essential branch of Wu, they painted the royal family’s ancestral figures and casted bronze crests of celestial beasts to accentuate the legitimacy and rightfulness of the emperors’ rulership.

Like the magical Xirang earth – a continuously self-expanding soil – which Gun used to barricade the flood, words possess this same ability to grow on their own. Symbols generate symbols; concepts derive concepts. A thousand years or so after, with the growing supremacy of words, the historians (a branch of Wu) rose in the status to that of an intellectual elite. While members of the former camaraderie, the dancers, the colloquialists, painters, and sculptors, kneel as its subservienence. This is how history of words and fine art unfolds; a tale of woefulness mixed with bitterness. But even more so, is the sense of nostalgia. To the good old days when words were not as overbearing as they are today. The days where Wū (the dancers), Zhù (the colloquialists) and Shi (the historians) could express their worldly views each through their expertise and lived in harmony. This tribute for the past is commonly shared among the three artists differentiated by their trajectories.

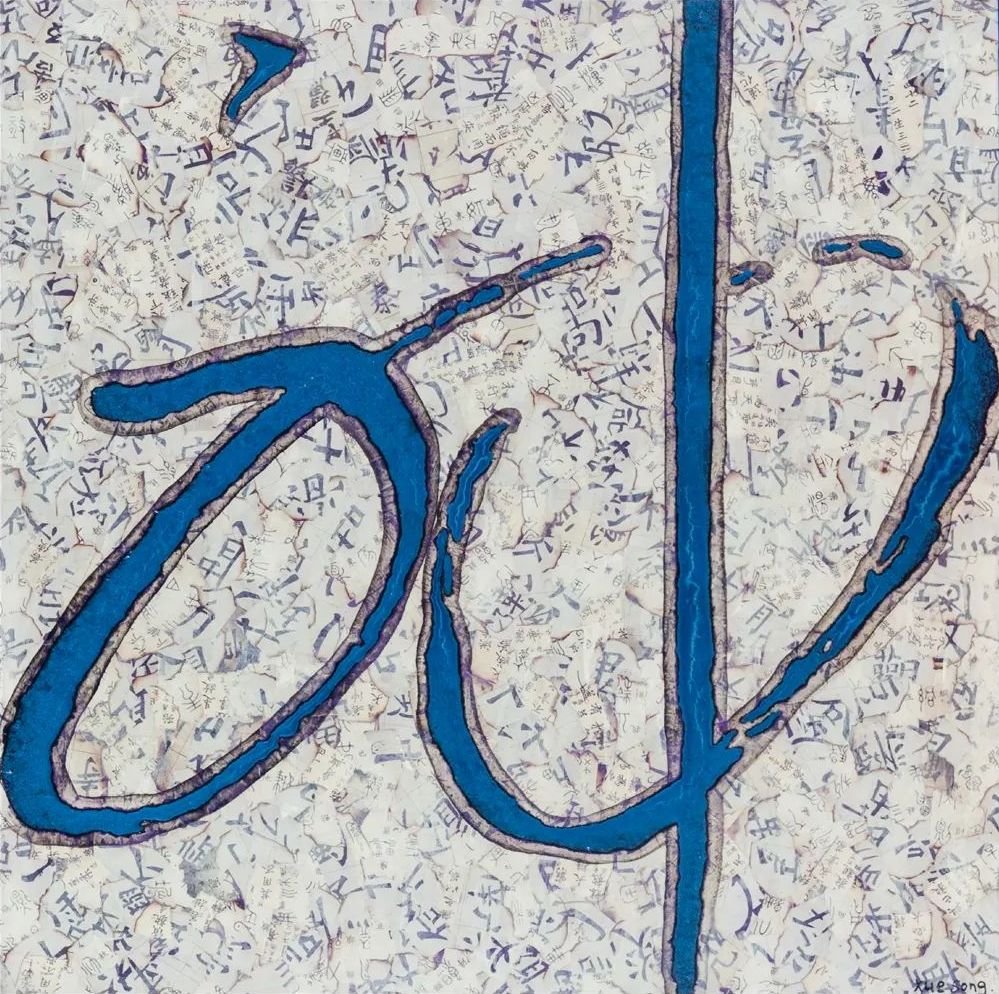

Pan Wei's approach is to loosen or even dissolve the referents of any textual symbols to allow the viewer, conditioned to decode the codes, to focus instead on the brilliancy of the characters. Xue Song, on the other hand, inverted the technique used in jinhūidūi to create word collage with a myriad of image sources such as: cigarette ads, stills from Chinese revolutionary operas, music scores, and even currency notes. It is remarkably satirical. Those who are well-versed semantically will certainly grasp his undertone expression with a heartfelt laugh.

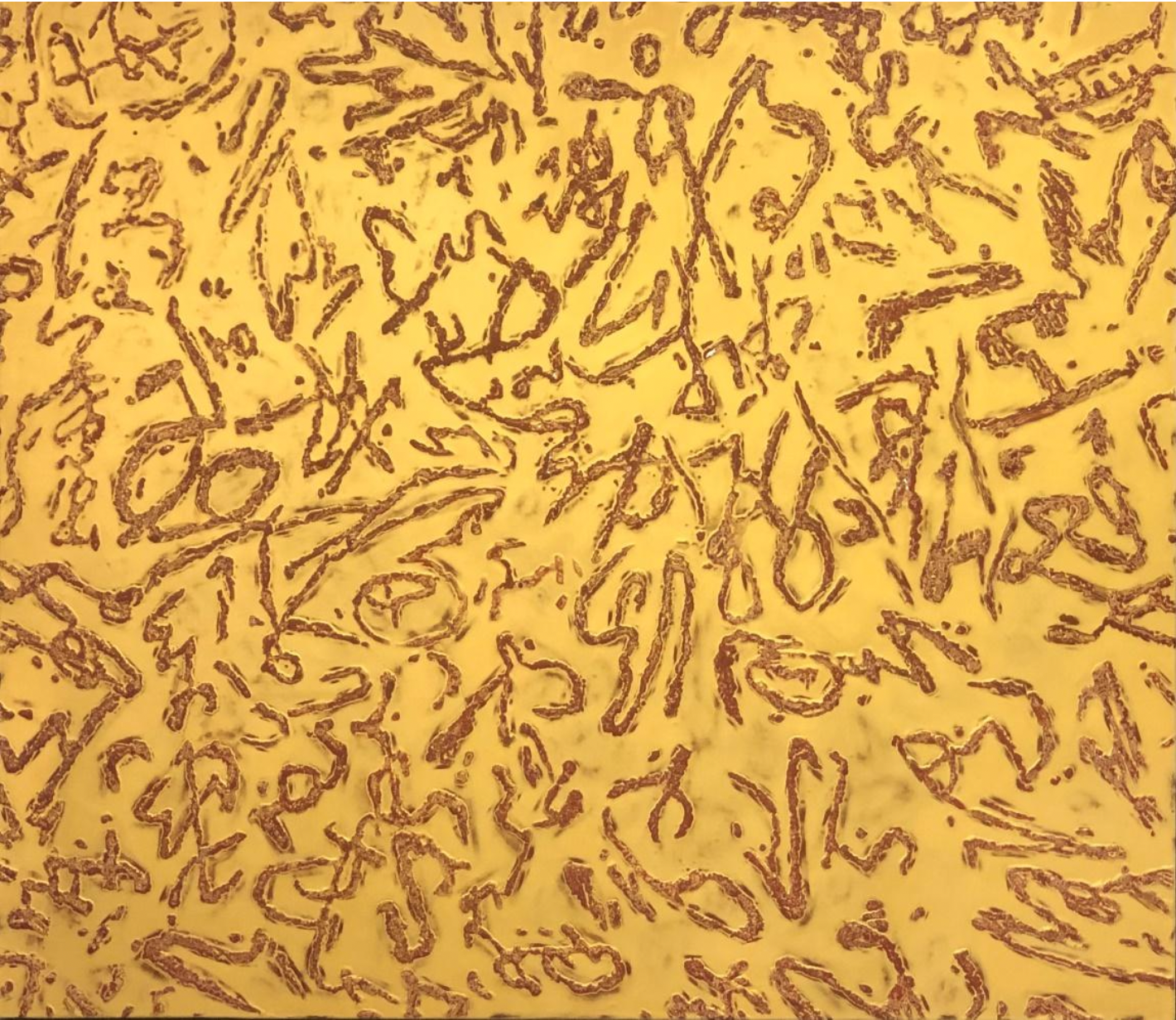

Huang Yuanqing's paintings does not appear to relate to words at first glance, but it is quite the contrary. His combination of brushstrokes and similar colour shades are like musical bars across his massive pictorial plane. Together, these basic units accumulate to compose the structure of his whole painting. In detail, his painterly dribbles transfigure the beauty of line impressions found in traditional Chinese calligraphy. Much like a Chinese opera singer singing spontaneously without a play script, Huang directs the viewer's focus on the rhythmic skills of speech, song, dance, and combat in movements instead. As the artist puts it, "Be attentive to the calligraphic expression in my work".

Words are self-propagating and self-abstracting. Since its invention, humankind has been acting like an overly enthusiastic child with a new water pistol, casting names on everything we set our eyes upon and inventing countless abstractive concepts that are impossible to pin in our physical world. We have essentially changed the world, along with ourselves. And in relation, changes to the nature and distribution of power. French Philosopher Michel Foucault once commented that it is by defining and classifying knowledge that intellectuals have achieved hegemony over the world. Over 7,000 years, words transformed the humankind; we became more humbled, yet more brutal, pretentious, and ultimately more morose.

Thankfully, the reign in words is not eternal, let alone omnipotent. For there is a realm that lies beyond words— sunny and bright with blooming flowers, basking in splendours and celebrations–it takes form in this merriment that is before us.

.▃

About the Artists

Huang Yuanqing

Huang Yuanqing's paintings examines the innate expressiveness of calligraphy in relation to modern and contemporary art. His practice primarily focuses on calligraphic abstraction. The artist welcomes elements of uncertainty and transience and the corresponding effects they ensue.

As one of the pioneers in China's abstract art scene, Huang Yuanqing integrates Chinese and Western techniques and approaches into his abstract paintings. Well steeped in calligraphy, the artist's paintings take a contemporary literati position to re-address the concept of "calligraphy and painting homology" in traditional Chinese art theory. Often, his works are crafted out of lines and layered with vibrant hues to produce a superimposed texture. The expressiveness of his calligraphic lines transverses through classical and contemporary, whereas the spontaneity of his brushstrokes-- lyrical yet precise--plays a symphony in consonance with the trajectory of time. Contrary to the principles of traditional calligraphy, he rarely finishes a painting in one sitting--individual works can take months or even years before completion. Suspending his artistic process and output, the artist thereby allows the painting to rewrite itself along with the sediments of time.

Pan Wei

Trained in calligraphy at an early age, artist Pan Wei uses his inherent knowledge and experience in the visuality of words to propose a new interpretation toward the genre. Here, words are no longer confined to traditional mediums paper and ink but painterly expressed with canvas and oil paint. It comes naturally for Pan Wei, who readily abnegates the original ideographic function of Chinese characters in his practice to invalidate the division between reading and seeing. By incorporating the visual found in ancient text into his works while distilling the literal meaning behind it, Pan Wei has created an artistic language that is remarkably his.

Xue Song

Xue Song is a contemporary Chinese pop artist born in 1965 in Anhui Province, China. Graduated from the Shanghai Drama Institute, Stage Design Department in 1988, he currently lives in Shanghai.

In 1990, a destructive fire swept through the artist's entire studio destroying everything in its path. Though devastating, the event marks an epiphany in the artist's future practice. From destruction to rebirth, it is like a cycle of reincarnation. The artist makes an extensive effort cutting and reassembling his candle-singed clippings from newspapers, books, and old photographs onto his canvas. In doing so, he sets these image fragments within the collage through a similar process of rebirth. They are released from their original context and given new interpretations. The artist has created his pronounced artistic language by combining Eastern and Western influence, historical memory, and the contemporary, traditional culture and modern ideologies into his collage.

Xue Song's works are in the collections of: Boston Art Museum, USA; University of Southern California Asia Pacific Museum, Bonn Museum of Modern Art, China Art Museum, Shanghai Art Museum, Long Museum, Hong Kong M+ Art Museum, Bill Gates Art Foundation and more.

.▃

Gallery View